February 29, 2024

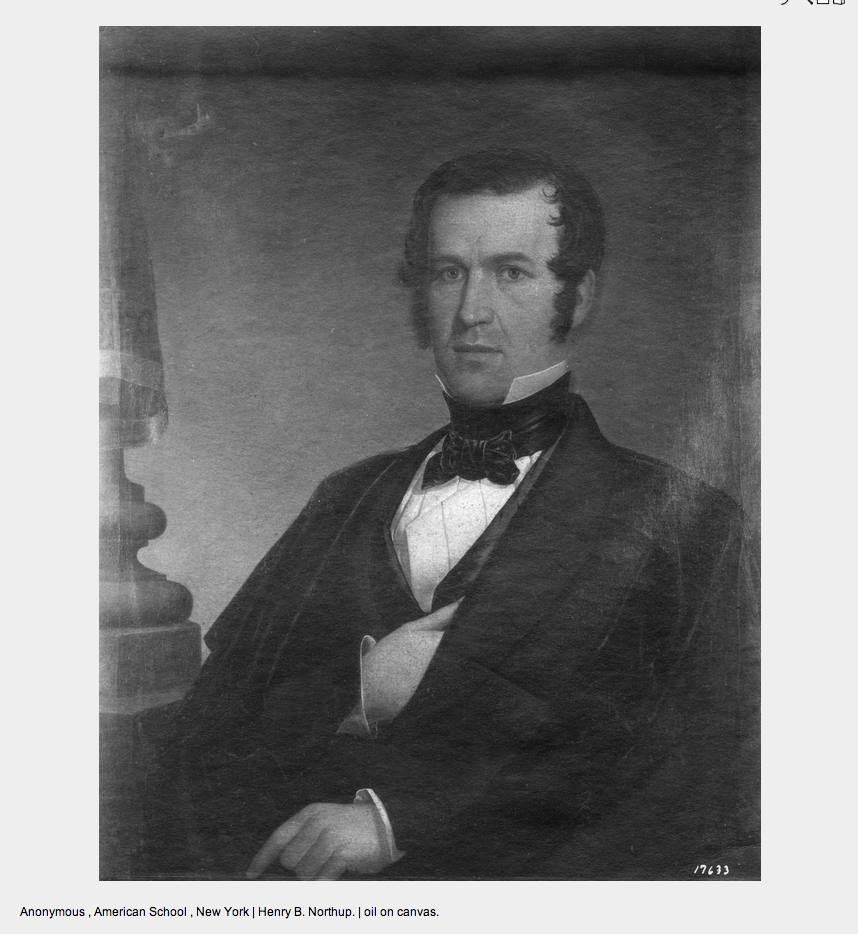

HENRY B. NORTHUP, THE MAN WHO RESCUED SOLOMON

“Henry B. Northup, Esq., of Sandy Hill, a distinguished counselor at law, and the man to whom… I am indebted for my present liberty… is a relative of the family in which my forefathers were thus held to service, and from which they took the name I bear. To this fact may be attributed the persevering interest he has taken in my behalf.”

This is how Solomon Northup introduces my great, great, great grandfather, in his compelling narrative Twelve Years a Slave.

In my case, however, I learned about him because I heard that Brad Pitt was going to play him in a movie. I think it’s fair to say that when you hear that Brad Pitt is going to play your ancestor in a blockbuster motion picture (touted as the emotional equivalent of Schindler’s List, you catch yourself glancing occasionally in the mirror). Here’s what I know about my relative. First, neither he nor I look the slightest bit like Brad Pitt.

But, Mr. Pitt and Director Steve McQueen deserve credit for the latest “rediscovery” of the Solomon Northup saga, and in a way continue the work of Dr. Sue Eakin. Moreover, the present-day attention that Hollywood is paying this story creates for us the opportunity to discuss the issues of slavery and race. This is particularly important to me as a resident of the U.S. Virgin Islands, the ancestral home of generations of descendants of former slaves. This is an opportunity to practice what Dr. King preached: “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.”

It is most important to remember: this is Solomon’s story. He was the victim, survivor and hero (in the classic sense) of his own narrative. The role played by Henry Bliss Northup, to me, falls into the category of “the least you could do”, and it seems Henry shared that categorization. He knew what was right and he used his significant political influence to make it happen. To understand his motivations, we must sift through what little we know about the family history and put everything in the perspective of the day.

The institution of slavery was not limited to the Southern plantations in the 18th and 19th centuries. Northern families held slaves, too. No doubt there were benevolent owners, just as there were tyrannical masters.

It was in this troubled world that the Northup family lived a life of Protestant piety and righteous work ethic. Henry’s parents, John Holmes Northup and Anna Wells Northup, moved from their home in Rhode Island to upstate New York around the turn of the 19th century. Accompanying them was a family slave named Mintus. Some accounts tell us that Mintus asked to go along, but the truth of his personal feelings are lost to time. In 1805, John and Anna had a baby boy they named Henry. Mintus and his wife (whose name is a mystery) had a boy of their own, some three years later. He was named Solomon, born a free citizen of New York State.

How these two families interacted is largely unknown. But, roughly twenty-five years later, John Northup died, freeing his slave(s) in his will. Mintus either asked to be named Northup out of respect and love of his former masters, or else that was the bureaucratic reality of the day, depending on whom you believe. What is certain is that Henry and Solomon were contemporaries, growing up together in the same household. That they should develop a brotherly devotion is no surprise.

Chapter XXII of Twelve Years a Slave recounts the reunion of these two men at Bayou Boeuf, Louisiana, in 1853. In my opinion, there is no more poignant, moving prose than this. That somehow, 160 years later, we are able to reflect on this incredible story is a credit to brave participants like Samuel Bass, generations of abolitionists, Dr. Eakin and her son Frank and countless other unnamed civil rights advocates. But mostly, we must recognize the outstanding actions of these two “brothers” named Northup.

As an aside, the decision to place Mr. Pitt in the role of abolitionist Samuel Bass and exclude Henry from the story is understandable. The confusion of surnames would be understandably difficult to explain in the final minutes of the film.

– Jeff Smith, St. John, VI